A Wizard Creates a Mountain; the Mountain Creates a Rain Shadow

One of the most enlightening things I’ve read on the topic of tabletop roleplaying games is an essay by Wolfgang Baur in The Kobold Guide to Worldbuilding, “How Real Is Your World? History and Fantasy as a Spectrum of Design Options.” It was this essay that clarified for me the distinctions among different types of fantasy, gave me a vocabulary to discuss them with and introduced me to what I consider the sweet spot—or at least my own personal favorite blend.

Most TTRPG players and fans of fantasy literature are familiar with the distinction between “low fantasy” and “high fantasy”: Low fantasy is the fantasy of George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire series or Ken Liu’s Dandelion Dynasty saga, in which (generally) the main characters are people of extraordinary competence but not people with extraordinary powers, living in worlds in which “people” are humans and magic is present but distant and rarely encountered by most. High fantasy is the fantasy of Andrzej Sapkowski’s Witcher series or N. K. Jemisin’s Broken Earth and Inheritance trilogies, in which the main characters possess supernatural gifts, humans live alongside other sapient species (if not always in harmony with them), and magic suffuses the world.

Low fantasy is often gritty and grubby and cynical, and high fantasy is often wide-eyed and optimistic, but it doesn’t have to be that way: The Dandelion Dynasty saga, for all its intrigue and war crimes, is cheery and hopeful at heart, while the Witcher series is as cynical as any tale of back-alley blackguards. What defines them as “low” or “high” is the degree of prevalence of the fantastic elements and the characters at the center of the action.

But low vs. high isn’t the end of the discussion. It’s just a small part of it.

To begin with, Baur’s initial distinction isn’t between low and high fantasy, but between “real” worldbuilding and “fantastic” worldbuilding. “Real” worldbuilding, which Baur divides further between “historical fantasy” and “real fantasy,” draws directly from our own world. Historical worldbuilding tells fantastic stories on Earth, at various places and times, either drawing from existing myth and legend or injecting new myths and legends into it. Susannah Clarke’s Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell, for instance, is a clear example of historical fantasy, being set in England around the time of the Napoleonic Wars. Shannon Chakraborty’s Daevabad Trilogy might be considered an example of what Baur calls real fantasy: While Daevabad is a wholly fantastic creation, it’s based in existing Arabian myth; it’s presented as part of our world, or at least adjacent to it; and the story begins in Cairo.

Fantastic worldbuilding, on the other hand, doesn’t need to have any connection to our world at all—neither our reality nor our myths. It’s wholly invented, built around a high concept, and any references to our world are by analogy, not direct. This rule holds as true in Westeros or Dara as it does in Cintra or Sky-in-Shadow.

There’s one further distinction to make, because there’s not just one kind of high fantasy. Baur draws a line between what he calls “wild-eyed wahoo fantasy” and “anchored fantasy.” Wild fantasy settings (I’m going to call them that, both for succinctness and as a matter of personal preference) are, in his words, “places where anything goes and the rules do not apply.” Anchored fantasy settings, by contrast, are places where not just anything goes, where rules do apply unless we explicitly say they don’t. They’re the synthesis of fantasy and reality. A jocular comment on the Mastering Dungeons Discord server by user Scipio202 (“You know, that mountain should really have a rain shadow … ” “Shut up, a wizard did it!”) helped me distill what I consider to be the essence of anchored fantasy: A wizard creates a mountain. The mountain creates a rain shadow. Magic exists, and it can perform miraculous feats, but anything that magic isn’t acting upon follows the laws of nature in its absence.

The Monsters Know What They’re Doing and all the books that sprang from it are, at heart, an extended exercise in anchored-fantasy thinking. The rules of the game are the natural laws of the game world. Whenever there’s no rule to tell us how things in the game world act, they act as they would in our own. When non-player characters make choices, and there’s no fantastic phenomenon to make them choose differently, they follow the same logic (or lack of it) that real people would follow. When creatures exist in the game world, they do so in ways that would allow them to continue to exist.

Why bother engaging in such thinking when everything is made up and the details don’t matter? Because, I would argue, the details do matter. The details are what make the world feel alive. They support immersion. An internally consistent and coherent world provides a backdrop to events that stand out because something about them doesn’t make sense. For us to marvel at the impossible, we first have to have some sense of the limits of the possible.

Anchored fantasy strikes a happy medium between everyday struggles in familiar milieus and mythic conflict in realms without rules. It facilitates journeys from the everyday to the incredible, and back again. It permits ordinary people to experience extraordinary things, and be changed by those experiences, and do extraordinary things themselves. It maintains room for whimsy, but it’s not dominated by it. It follows the laws of cause and effect, but it allows powerful arcane or divine forces to upend those laws—with meaningful and interesting consequences. It’s neither too real to be interesting nor too wild to invest in. It gives us something to gain and something to lose.

One of the things I think was and is most praiseworthy about fifth edition Dungeons & Dragons as it came to us in 2014 is that it comfortably accommodated all the different styles of fantastic worldbuilding: wild high fantasy, anchored high fantasy and low fantasy alike. It was easy to turn the dials and find the setting that your table liked best. Sadly, that hasn’t remained true with the 2024 rules revision, which has gone all in on wild high fantasy, not just in its art—although the art direction of the 5E24 core books communicates its partiality to wild high fantasy very clearly—but in the many new class features that make it abundantly clear that even a wet-behind-the-ears level 1 PC is already a sort of hero, not merely competent but special. You can try to play anchored high fantasy, or even low fantasy, using the 5E24 rules, but you’ll be fighting those rules the whole way, and they’ll be fighting you.

What bothers me about this total commitment to wild fantasy is its dilution of the fantastic. Even in the smallest villages and most remote hinterlands, characters live cosmopolitan lives, never batting an eye at neighbors or wayfarers with animal heads—or even devil horns and tails, despite the established existence of fiends who present a mortal threat to their lives and souls. Magic is a service that can be bought over the counter, and everybody’s got a little bit of their own. There’s so much magic in the world that it no longer feels magical.

Myth, magic and monsters are fascinating, but they’re fascinating because they’re unusual, because they defy our expectations. When they’re not only everywhere but everyday—commonplace, unremarkable—they lose their power to fascinate. The world becomes a different kind of mundane, a circus world in which nothing has to make sense and, therefore, there’s no meaning … and no stakes.[1]

Is it time for me to switch to another system? Perhaps, but which one? Kobold Press offers its own spin on the 5E system with Tales of the Valiant, but its rules also have a baked-in bias toward wild high fantasy. Pathfinder, an offshoot of D&D 3E, has always been an exclusively wild high fantasy system. Other designers have brought their own competing systems to the table this year, to tremendous applause and enthusiasm, and these systems offer … different sets of rules with which to play wild high fantasy.

What about old-school rules? I’ve enjoyed my brief excursions into Shadowdark and Knave, but for my meat-and-potatoes gaming, I’m not looking for an endless loop of dungeon crawling. I still enjoy telling big, sprawling stories that go unexpected places, stories of wonder and intrigue, stories that span the breadth of a world’s geography and delve as deeply into the alleys and subcultures of its cities, the hearts of its forests and the peaks of its mountains as they do into the warrens dug through its crust. It just so happens that I also like the idea that some people go adventuring simply because they can’t find work doing anything else, and they need to survive somehow. And I like imagining that while they do, their hometown might be dealing with such problems as a palisade-wrecking mudslide or a drop in demand for the byproducts of its copper mining, problems that are just as pressing to those townspeople as is the resurgence of a dragon-worshiping cult.

Cling to 5E14? I’m honestly not sure what other course presents itself. But 5E14 is now a legacy product, no longer officially supported by Wizards of the Coast and only halfheartedly supported by D&D Beyond (unsurprisingly, since it’s owned by WotC). No one’s going to write or design anything new for it except for their own home tables.

I’ve always been acutely aware that my preferences are out of step with those of the broader RPG-playing community. Even in 2012, when Baur wrote “How Real Is Your World?”—two years before the release of D&D 5E14—he noted, “Gritty settings are more appealing to designers than to players. Few players want limits to their characters’ power … . Design for low fantasy if you like, but realize that the majority of the fantasy RPG audience doesn’t play this style of game.” The OSR movement, along with Blades in the Dark and its offshoots, has since shown that the market for low fantasy is robust enough to cater to, but the biggest movers in the market are showing a clear strong preference not just for high fantasy but for high fantasy without limits.

I’ve always argued, and will continue to argue, that bounded creativity produces more interesting results than unbounded creativity, and I’ll always be grateful for the degree to which 5E14 supported that perspective (for its first five years of existence, anyway). But 5E14 is inevitably going to diminish and go into the West, and without a clear successor that accommodates an anchored-fantasy style of play, the TTRPG market is likely to wind up as polarized as the rest of our society, with a mass movement toward all wild high fantasy, all the time, on the one hand and a low-fantasy dungeon-crawling counterculture on the other. More’s the pity.

I’m not leveling this critique at Eberron, which Baur categorized as wild fantasy but which I think definitely has at least one foot in anchored fantasy, as it honestly and thoughtfully explores the logical implications of magic that’s understood well enough for it to be applied as a form of society-shaping technology. ↩︎

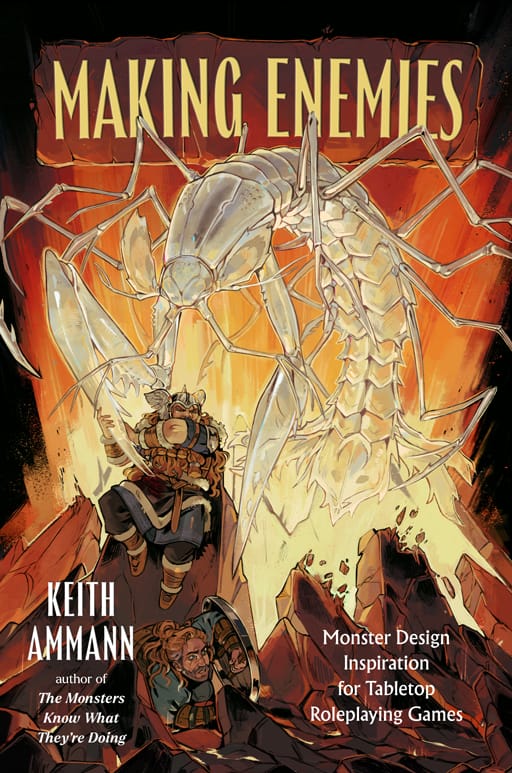

In The Monsters Know What They’re Doing, the essential tactics guide for Dungeon Masters, and its sequel, MOAR! Monsters Know What They’re Doing, I reverse-engineered hundreds of fifth edition D&D monsters to help DMs prepare battle plans for combat encounters before their game sessions. Now, in Making Enemies: Monster Design Inspiration for Tabletop Roleplaying Games, I explore everything that goes into creating monsters from the ground up: size, number, and level of challenge; monster habitats; monster motivations; monsters as metaphors; monsters and magic; the monstrous anatomy possessed by real-world organisms; and how to customize monsters for your own tabletop roleplaying game adventuring party to confront. No longer limited to one game system, Making Enemies shows you how to build out your creations not just for D&D 5E but also for Pathfinder 2E, Shadowdark, the Cypher System, and Call of Cthulhu 7E. Including interviews with some of the most brilliant names in RPG and creature design, Making Enemies will give you the tools to surprise and delight your players—and terrify their characters—again and again.

Preorder today from your favorite independent bookseller, or click one of these links:

Spy & Owl Bookshop (hi it me) | Barnes & Noble | Indigo | Kobo | Apple Books