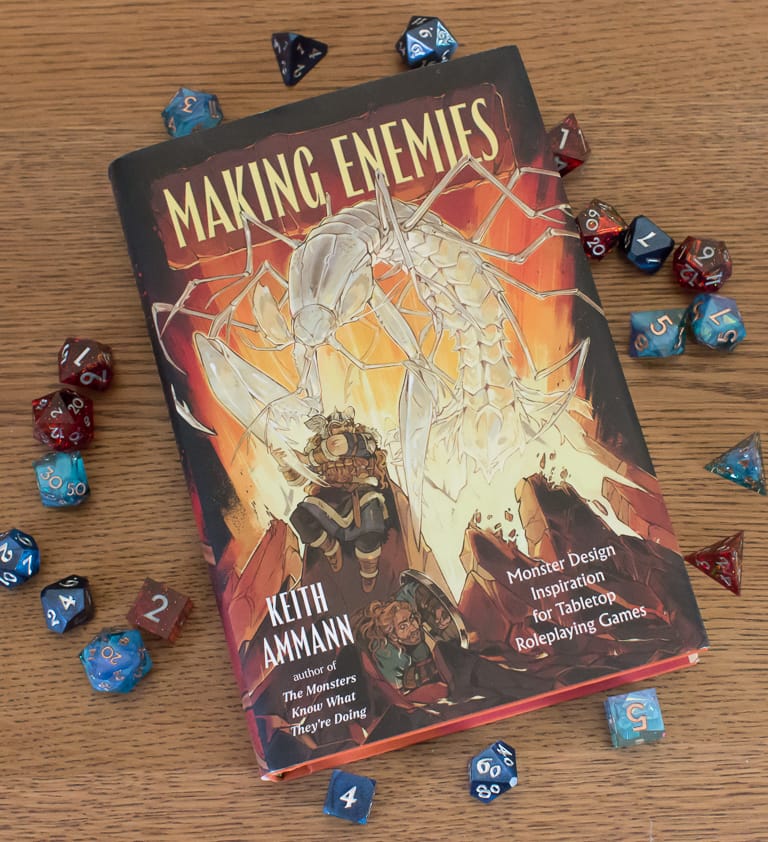

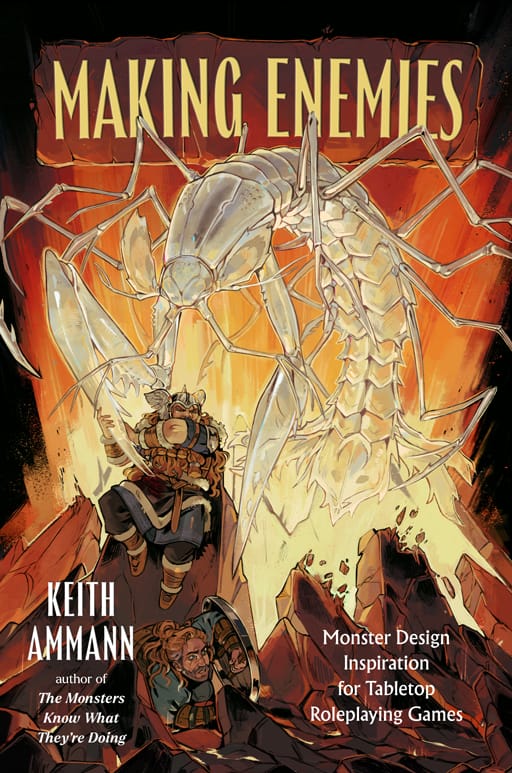

Making Enemies: Just One Month Away!

My latest title, Making Enemies: Monster Design Inspiration for Tabletop Roleplaying Games, is just 29 days away from publication! It’s been a long road and a long wait, but Making Enemies finally rolled off the presses last week, and on Friday I got to hold a copy in my hands for the first time.

In celebration, allow me to share with you an excerpt from the introduction of Making Enemies:

The Nature of a Monster

Confronting monsters is at the heart of the fantasy roleplaying game genre—and not just fantasy, but also horror, modern supernatural fiction, and occasionally science fiction (in which the “monsters” are sometimes aliens, robots, viruses, berserk computers, or antagonistic analogues from parallel universes). That confrontation often involves combat, although it doesn’t have to. Sometimes a monster can be overcome by charm, persuasion, a magical formula, trickery, scientific genius, or empathetic understanding rather than violence. Nevertheless, it must, somehow, be overcome.

So what is a monster? Here’s one definition: A monster is a frightening creature. That’s simple and straightforward—a bit too simple and straightforward. It includes common predators, animals with fearsome-looking but maladaptive mutations, and the bacterium that causes anthrax.

Yes, monsters are frightening, but they’re a particular kind of frightening, one that emerges primarily out of three elements:

They’re unfamiliar. Things we know how to handle, even when those things can harm us, aren’t scary. Scariness comes from the unknown.

Under normal circumstances, a monster is rarely seen. Its appearance heralds a change for the worse.

Whether barely glimpsed or suddenly ubiquitous, a monster is poorly understood. It’s not clear how the average person is supposed to escape it, resist it, or defy it. Even the harm it threatens may not be obvious on its face—but there’s something unsettling enough about it to provoke worry. It’s not in the script. Folks aren’t prepared to deal with it.

They’re dangerous. Being rarely seen and poorly understood, by itself, doesn’t make a monster. An exotic butterfly is not a monster unless it lands on your neck and starts sucking out your blood … or your memories. An unfamiliar creature with no mode of attack is merely a curiosity. A monster has to be able to cause harm, whether to life, liberty, reason, identity, reality, or something equally precious.

Intent doesn’t matter. A monster causing harm presents an immediate danger, even if the monster believes it’s doing something good. In fact, that dissonance often makes it worse.

They’re unnatural. A northern pike, even an especially big and aggressive one, isn’t a monster. Predatory animals are part of the natural order. On the other hand, a predator that starts killing excessively, or carelessly and messily, or with apparent malice or exceptional boldness—that is, in ways that have nothing to do with simple survival—might be considered a monster. So would a beast that’s normally considered prey if it turns around and goes after its former predators, other animals, or people. So would a plant that does anything except live its quiet, inert plant life. So would any creature whose nature and/or existence either can’t be explained or can be explained only in reference to anomalous forces or processes.

In general, a living thing that acts in ways we think it shouldn’t (or a nonliving thing that acts in any way at all) is a good candidate for the “monster” designation. Mind you, we’re not talking mere violations of social convention here, like tipping your server less than 20 percent. We’re talking about things that would never occur to most people, like wrapping captives in sticky protein fibers and presenting them to the great zikwimazira so that it can lay its eggs in their thoracic cavities. Whatever anyone else may have told you, that is not okay.

Out of the Blue

The No. 1 rule of monster creation is: Make it memorable.

A memorable monster surprises the players. There’s something unpredictable about its behavior, its appearance, its sensory capabilities, its size or strength or speed or intelligence, or its attempts at communication. It seizes the players’ attention and dares them to face the gap between their preconceptions and what’s actually in front of them.

Try to include something unexpected in every monster you create. In particular, if your player characters are meant to fight it, give it at least one unexpected attack and one unexpected defense.

In D&D, an “attack” is narrowly defined and has several parameters, including whether it’s melee or ranged, how far it reaches, how much damage it deals, and what kind(s) of damage it deals. Beyond the basic attack action, however, many monsters have actions that aren’t strictly defined as attacks yet are decidedly unneighborly: They cause damage over a wide area, create difficult terrain, grapple, restrain, charm, dominate, mesmerize, or otherwise exert some sort of undesired control. The Cypher System, on the other hand, defines an attack as “anything that you do to someone that they don’t want you to do”—and for the purposes of this suggestion, so do I. The point is, you can vary a creature’s hostile actions in thematic, flavorful ways, and when you do, it will make an impression on your players.

Similarly, defensive parameters in D&D and Pathfinder include Armor Class, movement, damage vulnerabilities or weaknesses, damage resistances and immunities, condition immunities, saving throw proficiencies, and unique traits (such as being able to Disengage as a bonus action or regenerate damage), whereas the Cypher System has just three defensive parameters—level, health, and Armor—but you have unlimited freedom to create conditions under which these values vary. Hit points and health aren’t that interesting to mess with, because all these parameters affect is how long a monster can keep fighting. Far more interesting are traits that grant reactions, extra movement, and other defensive responses to a hit—or a miss. A monster’s defenses should be exciting rather than frustrating. Fights against monsters that PCs can’t hit at all, or that are so tough that the PCs can land hit after hit on them without seemingly making any progress toward bringing them down, suck the fun out of combat.

A simple but somewhat cheesy way to juice up a monster’s apparent threat level is to choose one ability, feature, spell, or attack that an adventuring party tends to rely on heavily and make that monster resistant or immune to it. When the party predictably employs such an attack to try and deal with its foe, the failure of that attack will put the entire party on red alert, even if the enemy isn’t uniquely strong in any other way. Don’t overuse this method, though: It gets old very fast, especially if you’re not just blunting the impact of the attack feature but negating it entirely. If you do use it more than once, make sure you rotate whose ability is getting thwarted, so that no player gets the sense that you’re picking on them. And, of course, make sure that other methods of attack work just fine.

Another way to make monsters memorable is to repeat a motif. If you’re creating a hierarchy of several related monsters, pick a couple of foundational abilities, then build on them more and more at each step up the hierarchy. The weakest and most basic ones should be simple, conveying the core concept of your monster genus and nothing more. Mid-level ones should be variations on the theme: x as group leader, x as spellcaster, x with stealth, x with special equipment, etc. With the big cheese, take the core concept to its logical extreme.

Every Monster Is a Story

There’s no monster without a narrative purpose, a role to play in the saga of your world. It might be your primary antagonist, or an agent carrying out missions for your primary antagonist, or perhaps nothing more than a bit player—in the PCs’ tale.

Like every PC, however, every monster is at the center of its own tale. It has personal goals and motivations and spends its days pursuing them. What are they? You should know. Monsters that spend all their time in one location, effectively in suspended animation, as they wait for PCs to come along and fight them feel fake and add nothing of interest. Even rolling the dice to clobber them feels like a waste of time better spent on other things.

“There are six kaba guards in this room.” Yes, and? There are any number of details you might add to change this scene from a static set piece to a slice of life in your fantasy setting, something that gives you a better idea of what kabas are like. Here’s an oldie but goodie: The kabas are sitting around a table, gambling. One of them is cheating. The others are starting to catch on. If the PCs observe quietly, they might be able to catch the cheater in the act and call him out. For a moment, the other kabas are chiefly interested not in the PCs’ intrusion but in punishing the cheater. After they’ve given him a thorough beatdown, they turn their attention back to the PCs, no longer hostile but indifferent.

That one’s such a popular option, though, that to experienced players it might feel a bit stale. Here are some other variations to consider:

- Instead of shooting dice, the kabas are playing bridge.

- Two of the kabas are having a religious debate, one of them propounding the more thoughtful dogma of Kurnaz while the other insists on the eternal primacy of the mighty Tek-Gozlu. The others are listening, making affirmative noises when each of the debaters makes a good point, and occasionally heckling.

- The kabas have caught some toads and are racing them.

- Five of the kabas are griping about their pay and the working conditions. The sixth is telling them to shut up, or she’ll report them to the boss.

- The kabas are an elite unit that can’t be distracted from their task, no matter what.

- Guard duty is a plum job compared with the other responsibilities the kabas could be assigned to.

- The kabas are uniformed, and their outfits are tailored and spotless.

- The kabas are sharing some uncommonly good jerky that one of them brought to work.

- One of the kabas is giving another a really rad tattoo. By anyone’s standards, the artistry is impressive.

- The kabas are discussing a recent battle they took part in, which went badly for them. They’re still sore about it and proclaiming what they intend to do in reprisal. Some of their plans are more practical than others.

- The kabas are discussing their mutual admiration of an ally, who may or may not be someone (or something) that the PCs will encounter later.

- The kabas are discussing the merits of certain etiquette rules.

- The kabas are playing some kind of athletic game that there isn’t room to play properly, resulting in hilarious collisions with walls, furniture, and one another.

You can come up with all sorts of possibilities by focusing on a handful of facts describing the kabas, their situation, and their location. Every one of these details conveys information about kabas in general and these guards in particular, and some of them also convey information about the organization that employs them.

Moreover, showing the kabas in action gives PCs something to talk to them about, creating an opening for the situation to be handled through social interaction instead of combat. Monsters must be overcome, but combat isn’t always the best way to overcome them; in some cases, it may be the worst possible path to take. On the other side of the coin, if the PCs do opt for combat, the kabas’ activity may reveal a weakness that the PCs can exploit, or it may signal that one or more of the kabas might willingly defect or opt for surrender over death.

As often as not, alliances are matters of convenience. If a band of humanoids and a devil are working together, that doesn’t mean the humanoids will side with the devil on every question or vice versa. There may be tension between them. Observation and social interaction may reveal fault lines between what the humanoids and the devil want, and PCs can apply pressure to widen those faults, potentially cracking them apart. Even if they can’t permanently sunder the alliance, finding ways in which the PCs’ interests overlap with those of the humanoids—or those of the devil, for that matter—may provide opportunities for the PCs to get one partner to do something the other wouldn’t approve of. Whenever you create a monster, it’s always worth considering what, if anything, someone could bribe or blackmail it with.

Monster or Hazard?

Monsters need motivations, even if they’re as rudimentary as “find food” or “follow instructions.” Those motivations also have to give you, the DM/GM/Keeper/etc., choices to make. A “monster” with no goal that brings it into conflict with the PCs, yet hurts them if they get too close to it, is hardly a monster at all. It’s merely a hazard—a superficially living trap.

Contrast the cyclops Polyphemus in Homer’s Odyssey with the sirens. Polyphemus is clearly a monster. He eats several of Odysseus’s sailors, then goes about his own business for a while, trapping Odysseus and his crew in his cave with a boulder. Odysseus has to come up with a plan to defeat the cyclops when he returns and does so, employing a combination of combat and trickery. Polyphemus presents a solvable problem, but not a trivially solvable problem; it takes might, cleverness, determination, and patience for Odysseus to prevail. The sirens are creatures whose song lures sailors to their doom. It’s automatic: If you hear their song, you die. That’s it. You can’t negotiate with them. You can’t fight them. If you know how to get past them, though—by plugging your ears so that you can’t hear their singing—you’ve solved the problem. Death or a trivial solution, take your pick: The sirens are a hazard.

Right after encountering the sirens, Odysseus has to sail through a narrow water gap with peril on each side and choose his fate: lose six of his crew to Scylla, a many-headed horror who snatches sailors from their ships and devours them, or risk losing his entire ship and his life to the massive, treacherous whirlpool called Charybdis.

Charybdis, obviously, is a hazard. But what about Scylla—hazard or monster? Despite Scylla’s monstrous form, I’d say she’s also a hazard. Her location is known, and she never leaves that spot, even though by now everyone with a choice has the sense to avoid it. Surely she could feed herself better if she migrated to a busier shipping lane, but she seems to lack the free will to do so. There’s no bargaining with her, either—offering, for example, to throw her a netful of fish for dinner in lieu of sailors. She does what she does, and that’s that. For all intents and purposes, that’s a hazard, not a monster.

Hazards have their place, but there are lots of things that make more interesting hazards than monsters. If you’re going to create a monster, have a clear enough idea about what it wants and give it enough choices to make that it’s something more than just a hazard.

Upcoming Appearances

Oct. 10, I’ll be at the Book Cellar, 4736 N. Lincoln Ave. in beautiful Lincoln Square, Chicago, for a reading/signing beginning at 7 PM.

Oct. 12, I’ll be at my friendly local game store, Chicagoland Games, 5550 N. Broadway, Chicago, for a reading/signing beginning at 3:30 PM.

Oct. 16–19, I’ll be at Gamehole Con in Madison, Wis., and I’m running four events: one D&D game, one Pathfinder, one Shadowdark and one Cypher System. D&D and Shadowdark are full, but there are still open seats left in the Cypher and Pathfinder games. I’ll also be talking monster design with Charles Gannon, Kenneth Hite, Alan Patrick and Bryan CP Steele and RPG-related book publishing with Ben Riggs.

Nov. 21–23, I’ll be at PAX Unplugged in Philadelphia, selling and signing books Friday and Saturday from noon to 3 PM.

Feb. 5–8, 2026, I’ll have a signing table at Capricon 46, a science fiction/fantasy convention in Chicago. It’s a smaller event, and a not-for-profit one, so every new attendee gives it a boost.

I’m hoping to add at least one more convention to the schedule in March, so watch this space.

Preorder Making Enemies today from your favorite independent bookseller, or click one of these links:

Spy & Owl Bookshop (hi it me) | Barnes & Noble | Indigo | Kobo | Apple Books