Neither Reverence nor Contempt

In another century, I studied photography. My advanced photography and senior seminar classes were taught by Professor Sean Wilkinson, now retired. As someone who stumbled sideways into visual art, I initially didn’t have much of a cognitive framework or vocabulary for thinking about it and discussing it, and my classes with Sean provided this priceless foundation. (For a brief moment, I even considered pursuing a career as an art critic. The moment was brief.)

One handout from senior seminar struck me like a bolt from above. I haven’t stopped thinking about it for the past 32 years, and I still keep the original handout itself in my possession and refer back to it from time to time. It’s shaped my thinking in practically every sphere of thought and study. Although it’s specifically about art criticism (and secondarily about how art criticism gets short shrift in art education), the wisdom in it has always seemed to me to be almost infinitely applicable. I look at literature, at politics, at cultural movements and, yes, even at games through this filter.

I’ve wanted to share it with the public for a long time, but I didn’t have a suitable platform for it, and I didn’t have Sean’s permission. However, I created this newsletter as a place where I could not only promote my work but also delve into subjects that would be off topic for The Monsters Know What They’re Doing, so the platform has existed for a while. And just this past week, I finally got permission from Sean to share it.

The handout began with an essay, “Critical Observations,” and also included collections of quotations and definitions. Below I share “Critical Observations” in its entirety along with the one quotation that resonated with me more than any other.

This post is a radical departure from my usual topics, but to provide a slender tether back, I encourage you to reflect on how we think about tabletop roleplaying games, the frames we use to discuss them, the extent to which TTRPG “discourse” is (and isn’t) a form of criticism, and how the long, steady decline of criticism in journalism leaves us starved for examples of how to respond to creative work publicly, in thoughtful ways, as a form of teaching and shared learning.

Critical Observations

By Sean Wilkinson

Art criticism articulates an observer’s response to a work of art. The critic must give attention to the process of observation, and to the articulation of that process, no less than to the work that is observed.

The critic is responsible for being informed about the objects of his/her attention. The foundation upon which the critic constructs an appraisal should include knowledge that is both specific and contextual, contemporary and historical, technical and conceptual, subjective and objective. The practice of criticism therefore broadens and deepens learning about many subjects, not least of them the critic him/herself. We don’t know what we don’t know (or what we do know) until we attempt to articulate what we think we know.

Verifiable absolutes are not possible and should not be sought in criticism; critical appraisals can never be objectively proven “right” or “wrong.” Criticism may be, however, more or less informed, clear, insightful, and valuable. What matters is the intelligence of the views expressed, how well informed, persuasive, and insightful they are. We should ask of criticism is it perceptive, articulate, and thought-provoking, not is it correct, or do we agree with it. Even the best work may be subjected to poor criticism, and the best critics will offer us something of value even when they examine poor work. In both the work under consideration and the criticism of that work, the question of good or bad is less important than the question of whether or not our engagement with it is worthwhile.

Like/dislike tells the listener/reader nothing useful about a piece of work and little about the critic except his/her inadequacy at criticism. A declaration of like or dislike short-circuits the process of reflection and analysis upon which criticism must be founded; it attempts to leap directly to an evaluation for which no firm footing has been established. The easy luxury of like/dislike is the normal mode for casual looking. It may be the initial impetus that leads to further inquiry, which may in turn evolve into thoughtful perception, but in itself it does not amount to criticism.

The difference between like/dislike and criticism is the difference between reaction and response. Reaction is a narrowly focused reflex, an unthinking action based on a sharply limited set of fixed ideas, a matter of pushing a button, flipping a switch. Response is more deeply rooted, more firmly based; it is the result of consideration and appraisal, of an awareness of context and consequence. Response reflects an evolved understanding, one that stems from an integration of sensibility and knowledge, feeling and thought, intuition and rationality. We react to things that impinge on us, like swatting at flies, but we respond to things we care about. Worthwhile criticism is always based on genuine engagement with its subject, and it is therefore a form of response.

Critics may, among other things, analyze, argue, challenge, clarify, condemn, describe, defend, define, discuss, educate, evaluate, examine, explain, explore, inform, inquire, persuade, praise, reject, reveal, suggest, and theorize. Language is the standard tool for the performance of these functions. Among the primary responsibilities of the critic is the careful use of language. Language poorly used may obscure instead of illuminate, distract rather than focus awareness. Language reflects a critic’s values, learning, and perceptual ability as surely as it reflects a critic’s opinion.

The word “critic” and its various derivative forms come to us from the Latin word criticus, which comes from the Greek kritikos, an adjective that refers to the ability to discern and/or judge. Kritikos derives from krinein, which, in addition to discerning and judging, means to sift or to separate, and which is also the root word for “certain” and therefore “ascertain,” which means to find out or to learn. The word “crisis” also derives from this root, and it is as relevant to criticism as these other words. A crisis is something that tests us, that may make or break us, that provides an opportunity to discover how well prepared we are to meet a challenge. When we criticize, we test an artist’s work, and we test ourselves; we find out whether a work is strong or not, whether we are equal to the task of understanding it, and whether or not it is worth the trouble of trying to understand.

Henry James proposed that we ask three apparently simple questions about a work of art when we wish to form a thoughtful critical view: “What is the artist trying to do? Does he do it? Was it worth doing?” Too often we make the mistake of assuming that we do not need to consider the first two questions when, in fact, they may be difficult even to separate, let alone to answer.

We assume that we all see the same thing when we look at the same picture. This illusion persists even though we know we all see the world beyond the edge of that picture differently. A picture may impose a limited set of possible ways in which to see what it presents, but the latitude for interpretation remains extraordinarily wide. Until we understand what an artist was trying to do, and can form an intelligent appraisal of whether or not he/she succeeded in that task, we have no valid basis upon which to build an argument about whether or not it was worth doing.

The person who made a piece of work may not have the best insight about what and how it means; indeed, quite often the maker is the least well equipped to analyze his/her work. This may be especially true in the classroom when the work is likely to be fresh and relatively undigested, unconsidered. Yet we typically accept at face value what the maker says about his/her work. Consequently we may fail to exercise our own imagination, form our own questions, make our own judgments, and propose alternative interpretations.

More often than not, neither the critic nor the majority of the critic’s audience are engaged in producing the sort of work that is criticized. Within the classroom, however, the critic is usually a producer of such work, and the critic’s audience is usually composed of people who are also engaged in such work. Each condition—relative distance from production versus active engagement—offers both assets and liabilities. In the classroom and in other venues in which critics are producers of the work they criticize, discussions often become overweighted with personal dynamics. Pride, vanity, fear of rejection, embarrassment, defensiveness, and other manifestations of ego involvement understandably come into play under such conditions. This can add a vital dimension to discussion, but it can also make it difficult to engage in the most useful sort of critical debate.

The ability to make art, the ability to enjoy art, and the ability to criticize art are closely related yet substantially different from one another. Formal education is a flawed and minimally successful method for teaching anyone how to make art; the best it can do is to facilitate those who wish to make it and would do so anyway. The university also does a weak job of teaching enjoyment, since this aspect of art is rarely understood to include more than superficial levels of “appreciation.” Criticism, with its emphasis on research, scholarship, rationality, and articulate expression, is clearly within the academic tradition, yet in most art departments it is the least practiced and least valued of these approaches to art.

Reading, writing, and discussion are essentials of critical practice. The first two are usually absent from studio/production classes, and they are typically slighted in other areas of visual arts programs. Thus students who pass through several years of study in the arts commonly have only a vague and incidental awareness of, and very little actual experience with, fundamental tools for understanding their own work and that of other artists. The assumption that the making of art is, by itself, sufficient for the development of critical insight is demonstrably false. Far from detracting from the exercise of making images and objects, the lively and intelligent practice of criticism enriches and deepens that work.

Without significant attention to criticism and art history, the legitimacy of studying art within a university is very much open to question. Action constitutes only part of the process of making art; in order to be whole, the process also requires reflection, which is the ground of criticism. Informed and rigorous criticism (not to be confused with mindless likes and dislikes) must be added to traditional art education, which concentrates almost exclusively on developing technical skill and celebrating intuitive impulse.

A final note:

Criticism may begin with an individual work and move into theories about the phenomenon of art itself. From one particular picture the critic may go on to explore the nature of picture-making in general, thus enriching our understanding of both the object and the larger processes of thought and action from which it emerged.

Much contemporary criticism goes further still and is primarily concerned with the phenomenon of criticism itself. This process of self-examination turns further and further into itself until it becomes more properly the concern of philosophy (or politics or psychology) than of its original, ostensible subject. Semiotics, poststructuralism, deconstruction, and radical Marxist, Freudian, and feminist analyses, to name only a few, can be very interesting and even illuminating, but often they become so acutely focused on a predetermined agenda and so arcane that they offer little of value to artists. One is reminded of Barnett Newman’s famous remark, “Aesthetics is for artists like ornithology is for the birds.”

In studying a philosopher, the right attitude is neither reverence nor contempt, but first a kind of hypothetical sympathy, until it is possible to know what it feels like to believe in his theories, and only then a revival of the critical attitude, which should resemble, as far as possible, the state of mind of a person abandoning opinions which he has hitherto held. Contempt interferes with the first part of this process, and reverence with the second. Two things are to be remembered: that a man whose opinions and theories are worth studying may be presumed to have had some intelligence, but that no man is likely to have arrived at complete and final truth on any subject whatever. When an intelligent man expresses a view which seems to us obviously absurd, we should not attempt to prove that it is somehow true, but we should try to understand how it ever came to seem true. This exercise of historical and psychological imagination at once enlarges the scope of our thinking, and helps us to realize how foolish many of our own cherished prejudices will seem to an age which has a different temper of mind. —Bertrand Russell

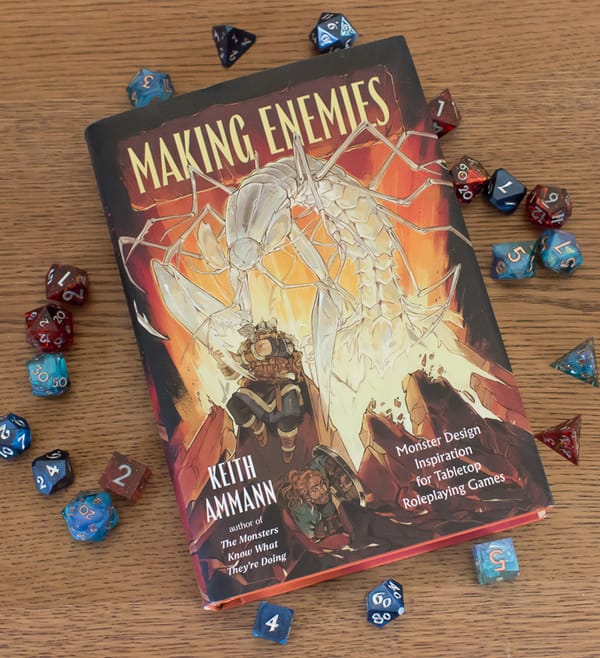

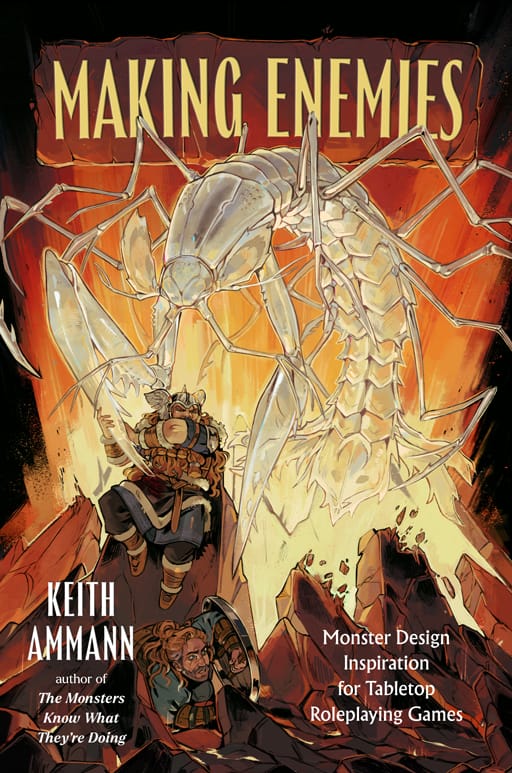

In The Monsters Know What They’re Doing, the essential tactics guide for Dungeon Masters, and its sequel, MOAR! Monsters Know What They’re Doing, I reverse-engineered hundreds of fifth edition D&D monsters to help DMs prepare battle plans for combat encounters before their game sessions. Now, in Making Enemies: Monster Design Inspiration for Tabletop Roleplaying Games, I explore everything that goes into creating monsters from the ground up: size, number, and level of challenge; monster habitats; monster motivations; monsters as metaphors; monsters and magic; the monstrous anatomy possessed by real-world organisms; and how to customize monsters for your own tabletop roleplaying game adventuring party to confront. No longer limited to one game system, Making Enemies shows you how to build out your creations not just for D&D 5E but also for Pathfinder 2E, Shadowdark, the Cypher System, and Call of Cthulhu 7E. Including interviews with some of the most brilliant names in RPG and creature design, Making Enemies will give you the tools to surprise and delight your players—and terrify their characters—again and again.

Preorder today from your favorite independent bookseller, or click one of these links:

Spy & Owl Bookshop | Barnes & Noble | Indigo | Kobo | Apple Books